Twenty years ago, planned sea exercises in the Barents Sea ended in a horrifying tragedy. There were two explosions aboard the Kursk submarine. The vessel sank. All 118 members of the crew were killed.

According to the official version, the sailors’ deaths were accidental, caused by a fault in a training torpedo. There is another version, however, that’s set out in the book “The Death of the Kursk”. Its author, Vice-Admiral , was part of the government commission set up to look into the catastrophe. Ryazantsev’s conclusions didn’t go into the official account, and he was dismissed.

We have visualized the causes of the tragedy described in the book.

Ryazantsev, Valery Dmitrievich – 25 years’ submarine experience, test torpedo specialist and commander of nuclear submarines. At the time of the Kursk tragedy was Russian Navy Deputy Chief of General Staff for Training, now a retired vice-admiral. Commandeered by the Defense Ministry to the Government Commission investigating the Kursk tragedy, though his conclusions didn’t go into the official report.Kursk – Pride of the Fleet

On August 10, 2000, The Kursk, a nuclear submarine, put out to see to take part in military Northern Fleet exercises. There were 118 seamen on board.

Annenkov Yuri

petty officer 2nd article of the contract service

Anikeev Roman

petty officer 2nd article of the contract service

Aryapov Rashid

lieutenant

Bagryantsev Vladimir

captain 1st rank

Baibarin Valery

midshipman

Baigarin Murat

captain 3rd rank

Balanov Alexey

midshipman

Bezsokirniy Vyacheslav

captain 3rd rank

Belov Mikhail

warrant officer

Belogun Viktor

captain 2 rank

Belozerov Nikolai

captain 3rd rank

Belyaev Anatoly

senior warrant officer

Borzhov Maxim

sailor

Borisov Andrey

senior warrant officer

Borisov Arnold

senior lieutenant

Borisov Yuri

sailor

Borkin Alexey

sailor

Bochkov Mikhail

warrant officer

Brazhkin Alexander

senior lieutenant

Bubniv Vadim

lieutenant

Vasilyev Andrey

lieutenant

Vitchenko Sergey

sailor

Vishnyakov Maxim

warrant officer

Vlasov Sergey

senior warrant officer

Gadzhiev Mamed Hajiyev

civilian expert

Geletin Boris

lieutenant

Gesler Robert

regardless of contract service

Gorbunov Evgeny

senior warrant officer

Gryaznih Sergey

midshipman

Gudkov Alexander

lieutenant

Druchenko Andrey

sailor

Dudko Sergey

captain 2nd rank

Evdokimov Oleg

sailor

Erasov Igor

senior warrant officer

Erahtin Sergey

lieutenant

Zubaidulin Resid

petty officer 1st article contract service

Zubov Alexey

warrant officer

Ivanov Vasily

warrant officer

Ivanov-Pavlov Alexei

lieutenant

Ildarov Abdulkadir

senior warrant officer

Isaenko Vasily

captain 2nd rank

Ishmuradov Fanis

midshipman

Kalinin Sergey

senior warrant officer

Kislinsky Sergei

warrant officer

Kirichenko Denis

lieutenant

Kichkiruk Vasily

senior warrant officer

Cazaderov Vladimir

senior warrant officer

Kozyrev Konstantin

warrant officer

Kokurin Sergey

captain-lieutenant

Kolesnikov Dmitry

captain-lieutenant

Kolomeytsev Alexey

sailor

Korobkov Alexey

senior lieutenant

Korovyakov Andrey

lieutenant

Kotkov Dmitry

sailor

Kubikov Roman

sailor

Kuznetsov Vitaly

senior warrant officer

Kuznetsov Vitaly

lieutenant

Larionov Alexey

sailor

Leonov Dmitry

petty officer 2nd article

Loginov Igor

sailor

Loginov Sergey

captain-lieutenant

Lyubushkin Sergey

lieutenant

Lyachin Gennady

captain 1st rank

Maynagashev Vyacheslav

chief petty contract service

Martynov Roman

sailor

Milyutin Andrey

captain 3rd rank

Mirtov Dmitry

sailor

Mityaev Alexey

lieutenant

Murachev Dmitry

captain 3rd rank

Naletov Ilya

sailor

Nekrasov Alexey

sailor

Neustroev Alexander

chief petty contract service

Nefedkov Ivan

sailor

Nosikovsky Oleg

captain-lieutenant

Pavlov Nikolay

sailor

Panarin Andrey

lieutenant

Paramonenko Viktor

midshipman

Polyanskiy Andrey

warrant officer

Pshenichnikov Denis

lieutenant commander

Rvanin Maxim

lieutenant

Repnikov Dmitry

lieutenant

Rodionov Mikhail

lieutenant

Romanyuk Vitaliy

warrant officer

Rudakov Andrey

captain 3rd rank

Ruzlev Alexander

senior warrant officer

Rychkov Sergey

warrant officer

Sablin Yuri

captain 2nd rank

Sadilenko Sergey

lieutenant

Sadkov Alexander

captain 3rd rank of the Cages

Sadovoy Vladimir

petty officer 2nd article of the contract service

Samovarov Yakov

warrant officer

Safonov Maxim

lieutenant

Svechkarev Vladimir

senior warrant officer

Sidyuhin Victor

sailor

Silogava Andrey

captain 3rd rank

Solorev Vitaly

lieutenant

Stankevich Alexey

captain of medical service

Staroseltsev Dmitry

sailor

Tavolzhanskiy Pavel

midshipman

Troyan Oleg

warrant officer

Tryanichev Ruslan

sailor

Tylek Sergey

lieutenant

Uzkiy Sergey

lieutenant

Fedorichev Igor

senior warrant officer

Fesak Vladimir

senior warrant officer

Fiterer Sergey

lieutenant

Halepo Alexander

sailor

Hafizov Nail

senior warrant officer

Hivuk Vladimir

midshipman

Tsymbal Ivan

senior warrant officer

Chernyshov Sergey

senior warrant officer

Shablatov Vladimir

midshipman

Shevchuk Aleksey

lieutenant

Shepetnov Yury

captain 2nd rank

Shubin Aleksandr

captain 2nd rank

Shulgin Alexey

sailor

Shawinskii Ilya

captain 3rd rank

Yansapov Salovat

regardless of contract service

118 crew members

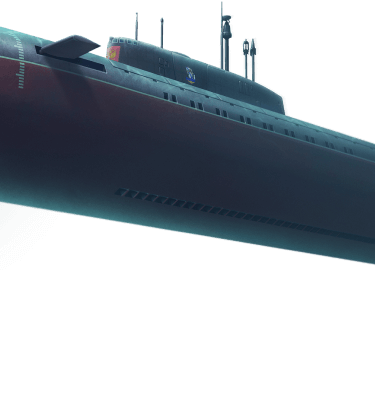

The Kursk was a 949A Antaeus design. That name was no accident – in Greek mythology, the giant Antaeus, the son of Poseidon, was undefeatable.

The vessel was specially developed to fight American aircraft carriers. It had 24 cruise missiles and 24 torpedoes. Each could destroy an entire ship. The submarine’s armoring was capable of withstanding underwater explosions. This was a beautiful and highly-developed piece of weaponry.

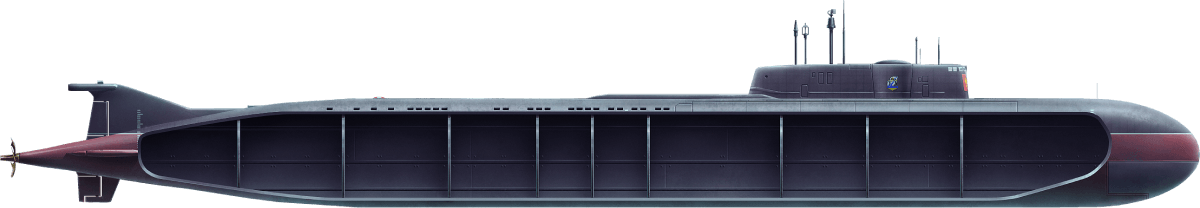

Designed to allow the seamen to survive in the event of a catastrophe. There is an emergency hatch here, through which the sub can be exited. There are survival kits for 120 men and food stores for six days.

The turbo-generator supplying the sub with electric energy and the equipment that powers the sub’s movement is located here. Underwater, the sub makes less noise than the sea itself.

The “heart” of the submarine. There are 2 nuclear reactors that allow the sub to go on voyages of up to 4 months (until food stocks run out). They have enough power to supply a sizeable city with electricity.

Decontamination area. This is where radio-active materials are removed from surfaces following work in the reactor compartment.

The diesel generator is located here, used if the turbo-generator fails, as well as the air regeneration apparatus.

This is where the seamen spend their free time. The galley, sleeping compartments and showers are located here, along with a sauna, gym and leisure room.

Responsible for the sub’s link with the outside world. This is where the apparatus that receives target coordinates from the fleet command is located.

The sub’s “brains.” The central command post is located here, and it is from here that the submarine is controlled.

The military capability of the sub. There are 6 torpedo launchers here, 28 torpedoes and several batteries. The torpedoes are stored on special racks and then loaded into the launchers with a special mechanism.

The Kursk’s mission is to track down its nominal enemy being played by the Peter the Great Cruiser and carry out training shooting. The seamen successfully launch a winged rocket, now it’s time for volley firing (launch of several torpedoes from several launching devices simultaneously). This was planned for August 12.

The sub’s crew is regarded as the best in the Northern Fleet. However, due to poor financing of the fleet in the 1990s, the seamen hadn’t even fired training torpedoes in three years.

A DIRTY BOMB

August 11th — the day before the firing – the seamen check the missile. This is a 65-76 “Kit” training torpedo. There are no explosives in it, though there is an aggressive fuel oxidant – high-test peroxide, which allows the torpedo to go faster and further.

The high-test peroxide provides the 65-76 with its advantage, but also its main danger. If the peroxide for some reason mixes with the hydrocarbon gases – evaporating off the engine oil, kerosene, the wire casings – there will be an explosion. Due to accidents, similar torpedoes in the USA and Great Britain were no longer being used.

The sensors indicate that one torpedo has to be filled with compressed air. This is a standard procedure, similar to pumping the tires on a car. The submariners hook the torpedo up to the sub’s air supply system with a flexible pipe.

The air supply system hadn’t been used on the Kursk for a long time. The pipe hadn’t been cleaned or degreased for years. Dust and old lubrication micro-particles had built up in it over those years.

The compressed air mixes with this dirt and fills the torpedo’s air reservoir. The training torpedo is transformed into a bomb.

INADVERTENT MISTAKE

On August 12th, the next day, between 9 and 10 in the morning, the seamen load the torpedo into the launching device. Before doing so they remove the torpedo’s safety-mechanism: they switch the cocking valve from “off” to the “ready to operate” position.

A characteristic of the 65-76 torpedo is that when the valve is switched it doesn’t necessarily fix itself in the correct position precisely. That allows the compressed air to react with the peroxide. This appears to be what happened with the torpedo on the Kursk.

According to the instructions, before loading the torpedo into the launching mechanism, the safety switch has to be checked.

Why didn’t the seamen check the dangerous valve? The answer is simple: They didn’t know what they were working with.

The crew had not used the peroxide torpedoes on the Kursk since its construction in 1995, which is to say never. Later the investigation would establish that the necessary instructions for the torpedoes weren’t even on board the sub.

Up to this point the dirty air had been kept apart from the fuel by the cocking valve. Now, due to the gap in the valve, the hydrogen peroxide began a violent chemical reaction with the particles of dirt. The pressure in the torpedo’s air reservoir began to rise.

EXPLOSION

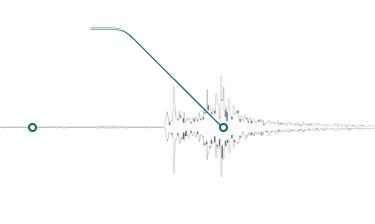

At 11:28 the trigger cylinder inside the torpedo exploded. This immediately detonates 1,500 tons of hydrogen peroxide mixed with kerosene. The powerful explosion was recorded by a seismic station in Norway.

Seven submariners in the 1st compartment die immediately from the blast. Through the hole in the roof of the torpedo mechanism the compartment is filled with water.

7 DEAD

111 ALIVE

Theoretically, there could have only been 7 victims of this tragedy. The sub could have gone into an emergency mode and surfaced. But that didn’t happen.

Antaeus class submarines have a specific feature in their design. When firing volleys from several weapons at once, the pressure in the torpedo section rises to such an extent that the seamen risk suffering contusions. To avoid this, before firing the torpedo crew unsealed their compartment, opening the ventilation between the compartments, in full accordance with their instructions.

The shock waves of the explosion pass through the ventilation ducts into the second compartment where the command station is located. The shock wave is weakened, but has sufficient force to inflict severe contusions and possibly deaths among the 36 submariners there.

7

3643 DEAD

75 ALIVE

The explosion causes the reactors and turbines to automatically shut down. The Kursk stops progress, only moving as a result of its momentum. Water fills the first compartment, and the sub begins to heel dangerous towards the bow.

SECOND EXPLOSION

A minute after the explosion, the angle of the heeling reaches 20°, in two minutes it is already 35°. After another 15 seconds, this multi-ton juggernaut hits the bottom. The full force of the blow is taken by the torpedo compartment.

At the moment of the collision, 10 live torpedoes explode with a force equivalent to 2 tons of TNT. This horrific explosion is recorded by seismographs all across Northern Europe.

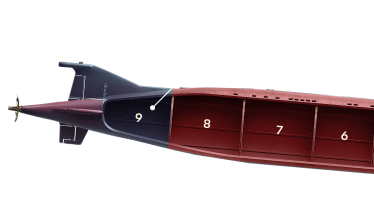

The Kursk ploughs on for about 30 meters and stops, having dug 2.5 meters into the seabed. The 1st compartment no longer exists. Neither do the 2nd, 3rd, 4th or 5th.

5-b – the reactor section – has been fitted with the toughest bulkhead, which stops the blast wave and suppresses its destructive force. It is only thanks to this bulkhead that the submariners in the 6th to 9th compartments are still alive. Of the 118 crewmembers, 23 remain.

43

5295 DEAD

23 ALIVE

SAFETY COMPARTMENT

The seamen make their way into the 9th compartment – the safety compartment – and hermetically seal it. There is already water in the compartment, however, which has got in through the technical piping. There is also fuel and technical oil in the water, which has spread through the sub following the explosion.

While the seamen block the leaks, a thin film of oil settles on the parts of the compartment.

The seamen don’t take any steps to abandon the submarine – they are confident that they will be saved. But no help comes. The air temperature falls to +4–7 degrees Celsius. There is not enough oxygen, and they breathe with difficulty. The emergency batteries run down, and the lights in the compartment die out.

At 15:00 the crew takes a decision to leave the submarine through the emergency hatch. In order to do that, a series of complex processes has to be carried out in total darkness. Firstly, oxygen is needed – at this point it can only be received from regenerative plates containing oxygen which have to be put into a special device.

The submariners find the plates in the darkness. This is their last, very slim chance. The plates can’t be used in premises where there is fuel or oil – if one drop gets on the plates by chance that will be enough for a fire that will burn at a temperature of up to 1000 degrees Celsius.

In total darkness, in a space covered in a film of oil, the submariners didn’t stand a chance. The fire flared up in an instant. There was no way to put it out, and the submariners didn’t have the strength anymore anyway.

95

23118 DEAD

not one alive

The submarine is found 17 hours after the explosion, when, according to Vice-Admiral Valery Ryazantsev, there were already no submariners left to save.

But what if the situation had developed in a different way and the submariners had waited for several days? Could a life perhaps have been saved?

A chronicle of the rescue operation gives an unambiguous answer to this question.